A child prodigy, virtuoso harpsichordist and renowned composer who lived during the reign of King Louis XIV, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre broke with the norms of her time and established herself as a major composer in the history of Baroque music.

Let’s discover the exceptional destiny of this musician of genius!

A precocious talent

Born in Paris in 1665, Élisabeth Jacquet was the daughter of Claude Jacquet, organist at the church of Saint-Louis-en-Ile (Paris), and the granddaughter of a harpsichord maker. Like her brothers and her sister, she began her musical apprenticeship with her father. Showing exceptional predispositions, she was presented to King Louis XIV at the age of five.

Dazzled by the little girl’s talent, the Sun King, a great music lover, encouraged his principal mistress at the time, Madame de Montespan, to take the little girl « three or four years with her to amuse herself pleasantly, as well as the people of the Court who visited her, in which the young Demoiselle succeeded very well ».(Titon du Tillet, Le Parnasse françois, 1732) She remained deeply grateful to the king, to whom she later dedicated almost all her compositions, and in turn she enjoyed royal respect and favor until the king’s death in 1715.

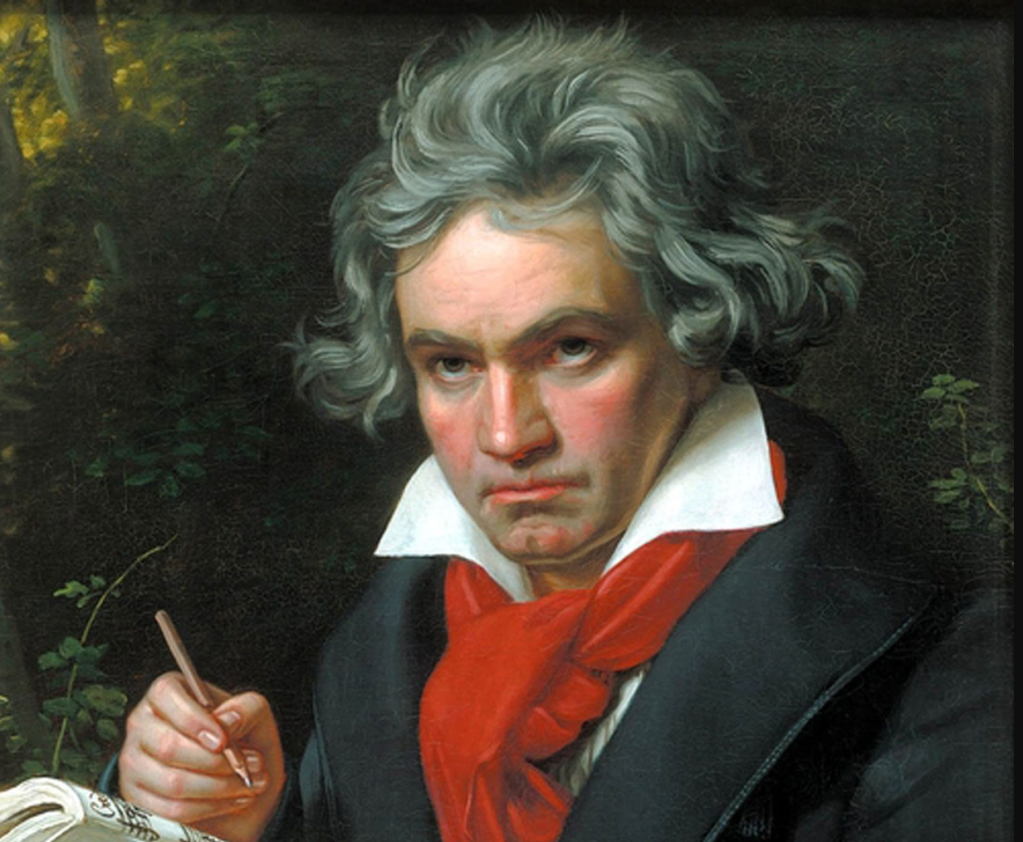

par François de Troy (1645-1730) – Coll. privée

First hits in Paris

In 1684, Élisabeth Jacquet married the organist Marin de la Guerre and moved to Paris with him. She gained recognition and esteem as a teacher and harpsichordist. Her success, as well as a royal pension, also enabled her: « Mme de la Guerre’s merit and reputation only grew in this great city, and all the great musicians and good connoisseurs eagerly went to hear her touch the harpsichord ». (Quoted by Catherine Cessac in an article to be read on the website Le clavecin en France)

However, she never held an official position at court, because at the time, as the musicologist recalls, « the social norms and socio-political customs that governed the recruitment of professional musicians did not yet allow Élisabeth Jacquet to hold any official position, whether at court or in the capital ». (Catherine Cessac, « Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665-1729) : femme compositeur ou compositrice ? »)

In addition to her performing talents as a harpsichordist and singer, Élisabeth also began composing. Her first works were short dramatic pieces produced for royal entertainment. Most of these have since disappeared, and the only surviving work from her early compositions is her opera-ballet Les Jeux à l’honneur de la victoire.

Her first publication dates from 1687, and his Premier livre de pièce de clavessin with unmeasured preludes: « These pieces are among the rare harpsichord collections published in France in the 17th century, along with those by Chambonnières, Lebègue and d’Anglebert », according to musicologist Catherine Cessac. The very fact that it was published during his lifetime is all the more exceptional as even for established male composers such as Charpentier it could be difficult to get published at the time.

As Cessac explains, the pieces in this collection are organized « into groups of dances with an already near-perfect arrangement that would become the model for the French suite: allemande, courante, gigue and final minuet, with the occasional addition of other dances (canaries, chaconnes and gavotte) ». Also included are unmeasured preludes and, unique for its time, a tocade, a French adaptation of the Italian toccata.

The failure of Céphale et Procris

In 1694, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre became the first woman to compose and have performed a lyric tragedy, Céphale et Procris. Inspired by Ovid and based on a libretto by Joseph-François Duché de Vancy, the opera was a resounding failure, and was withdrawn from stage after 6 performances.

With a prologue glorifying the king and five acts based on the model established by Lully and Quinault, Céphale et Procris suffers from a poorly constructed, clumsy libretto. The music, in the Lullist style, is both beautiful and expressive: « Throughout her imposing score (five acts preceded by the usual metaphorical prologue), the composer deploys all her expressive science, in both tragic and picturesque veins, under the aegis of the meeting of French and Italian tastes. » (Bénédict Hévry)

Personal loss and years of silence

Between 1694 and 1707, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre published absolutely nothing. Marked by the failure of Céphale et Procris, and distressed by the death of several relatives, including her only son, she entered a period of silence.

Yet her work continues to be circulated. In 1695, for example, the composer, musicologist and collector Sébastien de Brossard copied for his collection at least two sonatas that Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre had composed in her youth and sent to him out of friendship.

These sonatas are among the earliest French examples of sonatas for violin and continuo, and were published in 1707 as part of a larger collection of sonatas. According to musicologist Silvia Peruchetti, « the highly innovative character and the unique, sometimes daring, sonorities that distinguish the 1707 sonatas were quickly recognized by the public of the time« , notably by the Mercure galant, a highly influential periodical of the period. (Booklet of the album Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre: Violin sonatas 1-6, Pan classics)

Return to composition

After her husband’s death in 1705, she resumed composing, and between 1707 and 1711 she published a volume of Pièces de Clavecin qui peuvent se joüer sur le Viollon, as well as six Sonates pour le Viollon et pour le Clavecin, and two collections of spiritual cantatas. According to Catherine Cessac, these compositions are « the first known example of accompanied harpsichord music, preceding Dieupart’s Six Suittes de Clavessin by almost fifteen years ».

As for the cantatas, they were among the first of this genre to be composed in France, where there was resistance to adopting musical forms from Italy. As early as 1708, Jacquet de la Guerre presented six cantatas based on texts by Antoine Houdar de la Motte and inspired by biblical themes. Her cantatas are built on a « plan in three large recitative/air sections » « with the occasional addition of symphonies ».

« Élisabeth Jacquet nonetheless maintains a balance between the style proper to the genre and the restrained tone imposed by the subject. With these two books, she establishes herself as the composer most representative of this specific inspiration of the cantata, and contributes to renewing the repertoire of spiritual music in French, which at the time no longer seems to be very much in favor with composers. » (Catherine Cessac)

In 1715, for the first time, Jacquet de la Guerre dedicated a work not to King Louis XIV, who died on September 1, 1715, but to the Elector of Bavaria Maximilien-Emmanuel II, a keen music lover and bass viol player. The collection, entitled Cantates françoises, includes three profane cantatas, Sémélé, L’île de Délos, and le Sommeil d’Ulysse, inspired by mythological tales.

These late works show the composer at the peak of her art. « The exceptional aspect of Élisabeth Jacquet’s secular cantatas derives not only from their unusual size, but also from their form and the place given to the instrumental part. In the first and last pieces, which are close to opera, the musician even seems to have wanted to revive a genre in which she had often tried, but without the desired success. » (Catherine Cessac)

In 1715, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre returned to the stage with a comic duet entitled « Raccommodement Comique de Pierrot et de Nicole », which was performed at the Théâtre de la Foire Saint-Germain. This musical duet was part of Alain-René Lesage’s play La Ceinture de Vénus, which mixed dialogue with a variety of musical numbers. It was the first duet in fairground theater, featuring an argument and the reconciliation of Pierrot and Nicole, and it was also the composer’s first foray into comedy. This minor work contributed to the birth of a new genre that was to flourish in the 18th century: opéra comique.

Last years

After 1715, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre continued to compose, but at a less intense pace, and disappeared from public life. According to Titon du Tillet, she composed a major s acred work, unfortunately since lost, « a Te Deum with large choirs, which she had performed in 1721, in the Louvre Chapel « for the convalescence of King Louis XV, then aged 11″. (Catherine Cessac).

Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre died in Paris in 1729, leaving behind a rich and lasting musical legacy.

Conclusion

Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre was much more than a talented composer and harpsichordist. She was a pioneer who paved the way for women in the world of classical music, composing for a variety of genres at a time when women composers were confined to writing instrumental music and melodies.

An emblematic figure of French Baroque music, she was long overshadowed by musicologists, before being rediscovered by American musicologists such as Edith Borroff and Carol Henry in the 1960s, and in France thanks to the work of Catherine Cessac.

Laisser un commentaire